On February 8, 1913, George Andrew Reisner, director of the Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition, arrived with twenty-nine trained Egyptian  workers and their equipment at Merowe, the capital of the Dongola Province in northern Sudan. Reisner planned to explore the ancient Nubian sites between Kerma, by the Third Cataract of the Nile, and the Egyptian border at Wadi Halfa, in order to select a site to excavate. Having obtained the necessary permissions, he and his team arrived at Kerma on February 11, and Reisner was so impressed by what he saw that they remained there until April. So began the Nubian campaign of the Harvard-MFA expedition, which continued almost without interruption until 1932. Over almost two decades it excavated the most important archaeological sites in northern Sudan--Kerma, Gebel Barkal, Nuri, Meroe (Begrawiya), and the Second Cataract Forts--and established the basis for all future work in the region.

workers and their equipment at Merowe, the capital of the Dongola Province in northern Sudan. Reisner planned to explore the ancient Nubian sites between Kerma, by the Third Cataract of the Nile, and the Egyptian border at Wadi Halfa, in order to select a site to excavate. Having obtained the necessary permissions, he and his team arrived at Kerma on February 11, and Reisner was so impressed by what he saw that they remained there until April. So began the Nubian campaign of the Harvard-MFA expedition, which continued almost without interruption until 1932. Over almost two decades it excavated the most important archaeological sites in northern Sudan--Kerma, Gebel Barkal, Nuri, Meroe (Begrawiya), and the Second Cataract Forts--and established the basis for all future work in the region.

The land of Nubia straddles modern-day Egypt and Sudan. Reisner's involvement with the area began in 1907, when he was asked by the Egyptian government to  record and excavate all the ancient cemeteries along the ninety-five-mile stretch of the Nile Valley in Egypt--from Shellal south to Wadi el-Sebua--that were to be flooded when the Old Aswan Dam was heightened to increase the volume of water in the reservoir it contained. That project, known as the Archaelogical Survey of Lower Nubia, focused on the early history of Nubia, as yet little known, and its relationship with Egypt, and resulted in the identification of a number of distinct cultural phases. The historical questions raised by the survey motivated Reisner to excavate in Sudan.

record and excavate all the ancient cemeteries along the ninety-five-mile stretch of the Nile Valley in Egypt--from Shellal south to Wadi el-Sebua--that were to be flooded when the Old Aswan Dam was heightened to increase the volume of water in the reservoir it contained. That project, known as the Archaelogical Survey of Lower Nubia, focused on the early history of Nubia, as yet little known, and its relationship with Egypt, and resulted in the identification of a number of distinct cultural phases. The historical questions raised by the survey motivated Reisner to excavate in Sudan.

Reisner was a pioneer in the use of photography to document every stage and every facet of archaeological fieldwork. In the beginning he took his own photographs and developed them himself. Assisting him in the darkroom was an Egyptian village boy, Said Ahmed Said, who quickly learned how to develop negatives and make prints. In 1901 Reisner turned over the darkroom work to him. By 1906 he had trained him to take photographs as well and made him responsible for all the photographic work of the expedition. In 1908 Said Ahmed was promoted to head reis (foreman); by that time he had started to train other boys, so from then on a succession of Egyptian photographers worked for the expedition. At a time when even Western-trained photographers were rarely credited for their work, Reisner proudly mentioned his Egyptian photographers by name in his publications.

The equipment involved was formidable: box cameras mounted on tripods, carriers for different size plates of film, multiple lenses, and tipping tables for angling the  camera up or down (chiefly down, for graves or groups of objects). The photographers used a heavy, large-format camera capable of handling full-size glass plates ( 7 x 9 inches, about 18 x 23 cm), as well as half plates (5 x 7 inches, about 13 x 18 cm) and quarter plates (31/2 x 41/2 inches, about 9 x 11.5 cm). They also used a smaller camera for half and quarter-size plates only. The expedition had two of each kind of camera, one for use in the field, the other in camp. The large format was preferred for general site views and landscapes. The wealth of detail and range of shading that could be captured by an experienced photographer is astonishing. For informal shots of the men at work, of people and places encountered on their travels, of incidents at camp, and of themselves, the photographers used a small-format hand-held Kodak camera. For our purposes these images are often among the most interesting.

camera up or down (chiefly down, for graves or groups of objects). The photographers used a heavy, large-format camera capable of handling full-size glass plates ( 7 x 9 inches, about 18 x 23 cm), as well as half plates (5 x 7 inches, about 13 x 18 cm) and quarter plates (31/2 x 41/2 inches, about 9 x 11.5 cm). They also used a smaller camera for half and quarter-size plates only. The expedition had two of each kind of camera, one for use in the field, the other in camp. The large format was preferred for general site views and landscapes. The wealth of detail and range of shading that could be captured by an experienced photographer is astonishing. For informal shots of the men at work, of people and places encountered on their travels, of incidents at camp, and of themselves, the photographers used a small-format hand-held Kodak camera. For our purposes these images are often among the most interesting.

These photographs were not taken for commercial purposes or as art. They were taken specifically to record the progress and the results of the excavations, and their highest destiny was to be reproduced in the published excavation report. Reisner gave detailed instructions on how to photograph an archaeological site. After the plates were developed and approved, two sets of prints were made.  One set was filed numerically by size, and the other set was mounted on cardboard and organized by site, comprising views of the excavations and the objects photographed in camp, to be annotated by the archaeologists. Selected images were then chosen to be reproduced in scholarly journals and eventually, after being cropped to show only what was needed to illustrate the point, in the final excavation reports.

One set was filed numerically by size, and the other set was mounted on cardboard and organized by site, comprising views of the excavations and the objects photographed in camp, to be annotated by the archaeologists. Selected images were then chosen to be reproduced in scholarly journals and eventually, after being cropped to show only what was needed to illustrate the point, in the final excavation reports.

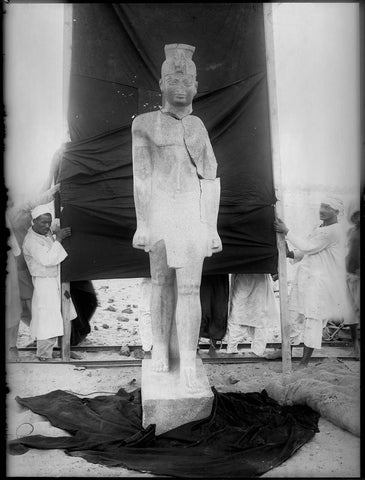

Showing the best of these images complete, outside their original strictly documentary context, brings the settings in which they were made to life and reveals the artistry of their makers. In these photographs, scientific rigor and artistic perception happily coexist.

Originally published in Unearthing Ancient Nubia, written by Lawrence M. Berman, Norma Jean Calderwood Senior Curator of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art. Edited for the web by Jacob M. Rochford and Maggie Loh.

We've selected some of the highlights of this vast collection of negatives from Nubia and Giza to be available to order as prints. Please contact us for custom orders of other excavation photographs not featured on MFA Prints.

Unearthing Ancient Nubia

Posted by MFA Prints on